Approach to Chest Pain, an Overview

Summary

Chest pain is one of the most common presentations in the emergency department and should be managed according to the cause and severity as it may develop adverse outcomes in regard to morbidity and mortality. It is the second most common cause, after abdominal pain, of visits to the emergency department by adults (especially old age patients).

Chest pain may occur due to many causes involving the cardiovascular (CVS), digestive, respiratory, and neuromuscular systems. Therefore, it is important to have a thorough understanding of all the possible causes and treatments. In this article, we will discuss an overview of all the diseases that can lead to chest pain, how to diagnose them, and their treatment in both the emergency and the outpatient departments (OPD).

Introduction

Chest pain is a challenging presentation in the emergency department, and it is after abdominal pain, the second most common cause of visits to the emergency department by adults (especially old age patients) (1). In most cases, it is due to benign causes, and it is of paramount importance not to ignore life-threatening diseases such as myocardial infarction, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, or pneumonia (2). Patients may complain of visceral pain, presenting as dull, squeezing, chest tightening and pressure, or somatic pain, presenting as sharp and stabbing in nature (3). Every system that could be involved in a patient presenting with chest pain (for example, CVS, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or musculoskeletal) must be assessed properly to improve management.

Epidemiology of Chest Pain

Approximately 4.7% of all emergency cases in the United States involve chest pain making more than 6.5 million visits per year. (4) Moreover, 4 million visits per year to the OPD are also due to complaints of chest pain. (5) Similarly, 6% of the patients (almost 7 million) attending the emergency department in England and Wales are due to the same complaint. This puts a massive burden on healthcare departments, as two third of these are admitted for evaluation and management. (6)

Previously, it was considered that chest pain due to angina is more common in men than in women. Nevertheless, recent studies prove that angina is equally common in both sex groups but the symptoms differ in women, showing more subtle or unspecific signs and symptoms and often termed as atypical angina, leading to misdiagnosis. (7) Similarly, chest pain due to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is greater in males due to its higher prevalence (9.2%) relative to females (6.2%), having a ratio of 1 to 0.67. (8) These differentiating factors should be kept in mind while dealing with chest pain in the emergency department.

Etiology of Chest Pain

Chest pain may be due to different causes involving the CVS, respiratory system, digestive and musculoskeletal systems. The approximate prevalence of each common condition presenting with chest pain is as follows:

Cardiovascular System

The most important of these etiologies is acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and almost 31% of chest pain cases are due to this group of conditions. It is also important due to its severity and prognosis, as it may lead to recurrence and even death if not given proper treatment. Other cardiovascular causes include pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, and aortic dissection making up 4%, 2%, and 1% of cases, respectively. (4, 9)

Respiratory System

Causes of chest pain involving the respiratory system include pneumonia (2%-4%), pleuritis, COPD, asthma, and pneumothorax. (9) Pneumonia is common both in children and adults but rarely presents as chest pain. Acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD are common. They are also important because the patient usually presents with difficulty breathing and decreased oxygen saturation, demanding immediate treatment.

Gastrointestinal System

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common non-cardiac cause of chest pain, and it makes up 30% of the cases. It is usually benign and can be treated with medication without developing any short-term complications. Esophageal tears or spasms may also occur but are less common. (9) Cholecystitis and gallbladder stones may also cause chest pain, but it is rare and usually present with abdominal pain and vomiting.

Musculoskeletal System

It is the second most common non-cardiac cause (28%) after GERD. It includes costochondritis, precordial catch syndrome, Tietze’s syndrome, stress fractures, and rheumatoid arthritis. (10)

Pathophysiology of Chest Pain

It depends on the underlying cause of chest pain. It may be due to infection or inflammation of the pericardium and pleura visceral layers or parenchymal structures (as in pneumonia, pleuritis, and pericarditis) (9). Blockage of blood vessels and decreased blood flow to heart muscles leading to necrosis is the underlying pathophysiology of ACS (10, 43). Atopy and increased response of the respiratory tree to allergens are responsible for asthma (27). Musculoskeletal pain may be due to muscle stretch, inflammation, or fracture.

History and Associated Signs and Symptoms

- Complete history and evaluation of risk factors are very important in the accurate diagnosis of patients presenting with chest pain. Historical data includes the onset and duration of pain, location, and radiation, aggravating and relieving factors, and previous episodes of similar pain (4). Associated symptoms may include shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, or an altered state of consciousness (4, 11).

- Symptoms that indicate the cardiac origin of pain include pain, particularly on the left side, radiating to the left arm, shoulder, or jaw with dyspnea, chest tightness, diaphoresis, fatigue, and syncope. The onset of pain is sudden, usually diffuse, and is aggravated by exertion (12, 13). In patients with sudden onset of stabbing and sharp chest pain radiating to the back, accompanied or not by vegetative symptoms, aortic dissection should be suspected. Low blood pressure and weak pulse are also indicative of cardiovascular involvement. (14) Previous history of any cardiac event, hypertension, and other comorbidities and risk factors should also be noted.

- Chest pain associated with cough (with or without sputum), fever, dyspnea, and rhinitis may support pathology involving the lungs and the respiratory tree. Fever and cough with sputum are usually present in pneumonia. Dullness on percussion and crepitation on auscultation also support the diagnosis (15, 16). Episodic symptoms and signs of atopy may indicate asthma with wheezing and rhonchi on auscultation of the chest (17). COPD also presents with the same symptoms but has a long-duration of symptoms with a history of smoking and old age mostly (18). History of blunt trauma or stab wound to the chest and breathing difficulty associated with chest pain makes ground for the diagnosis of pneumothorax (28).

- Gastrointestinal involvement with chest pain is usually denoted by the presence of heartburn, dyspepsia, regurgitation, and bloating, which is aggravated by eating, indicating gastroesophageal reflux disease and sometimes peptic ulcer disease (19). Gallbladder stones and cholecystitis also present with almost the same symptoms, with pain radiating toward the right subcostal region or right shoulder tip. In some cases, chest pain may present with hematemesis and pain radiating to the epigastric region. This leads to suspicion of esophageal tear or Mallory Weiss syndrome (20).

- If the chest pain worsens on movement, changing positions while lying, or even during deep breathing movements, then costochondritis or musculoskeletal involvement must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It may be sharp or dull pain due to inflammation of the cartilage joining the sternum and ribs .(21) Vital signs are usually within the normal range. Rheumatoid arthritis usually presents with systemic symptoms, morning stiffness, and involvement of other joints.

Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

Any disease which may have chest pain as its presenting symptom must be included in differential diagnosis so that there is no possibility of misdiagnosis. These include myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, aortic dissection, pericarditis, pneumonia, pneumothorax, asthma, COPD, GERD, peptic ulcer disease, esophageal tear or spasm, cholecystitis, gallbladder stone, costochondritis, Tietze’s syndrome or rib fracture.

Investigations

The choice of investigation depends on the history and associated symptoms. Investigations are very important to confirm the diagnosis and rule out life-threatening diseases. So, it should be cost-effective and according to the situation. Each system should be evaluated separately. The most useful and important investigations for chest pain are as follows:

Cardiovascular System

- ECG is the first and most important investigation which should be done in every patient with chest pain to assess acute coronary syndrome (ACS), which has high sensitivity and specificity when specific findings for myocardial infarction are encountered. Myocardial ischemia is represented by ST-segment elevation, which is the hallmark sign. Although non-ST-segment elevation, myocardial ischemia can also occur. (13) Troponin assays are the next best step for ACS diagnosis. High-sensitivity assays are considered more specific than conservative troponin assays (22).

- D-Dimers are commonly used for the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection. Contrast-enhanced CT scan is the standard of care in diagnosing aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism. A transesophageal ultrasonogram (USG) can also be done for accurate diagnosis but is usually skipped in emergency conditions. (23, 24)

Respiratory System

- X-ray chest is the first step in the evaluation of the respiratory system and lung pathology, as many diseases can be diagnosed with this basic investigation, and it also helps in assessing for other causes of chest pain, such as those of skeletal or mediastinal nature. Pulmonary Infiltrates on X-ray (with correlating clinical symptoms) can lead to the diagnosis of pneumonia. (25)

- While the presence of hyperinflation, increased anterior-posterior diameter, and a flat diaphragm point toward COPD. Spirometry and pulmonary function testing (PFT) are useful in assessing obstructive diseases such as asthma and COPD. The FEV1/FVC ratio (forced expiratory volume in one second/Forced vital capacity) of less than 0.7 confirms obstructive disease (26, 27). The reversibility in FEV1/FVC ratio with salbutamol is diagnostic for asthma (27). Eosinophilia on complete blood count is also supportive of asthma (27).

- Pneumothorax can be diagnosed with chest X-ray (air space in lung field) and USG of the chest. Approximately 2.5 cm of air space in the lung field is diagnostic for pneumothorax in at least 30% of cases (28).

Digestive System:

- Abdominal USG is the recommended initial investigation and may help in diagnosing cholecystitis and gallbladder stones due to its accuracy and non-invasive technique (29).

- GERD is usually diagnosed clinically, but upper digestive tract endoscopy is used for cases not responding to treatment and for tracking associated complications. Esophageal sphincter manometry is rarely used. (30)

- Upper digestive tract endoscopy is also the gold standard investigation for esophageal tears and varices (20).

Musculoskeletal System:

Musculoskeletal chest pain is usually diagnosed on the basis of signs and symptoms and ruling out other life-threatening diseases. Vital signs and investigations done for other diseases (like ECG, troponin assays, endoscopy, and pulmonary function tests) are usually within normal range. (31)

- An X-ray can be useful in cases of rib fractures.

- Rheumatoid arthritis can be detected by RA factor, elevated C-reactive protein, and ESR.

Diagnostic Criteria in Patients with Chest Pain

The diagnosis is made by correlating presenting complaints, signs and symptoms, and investigations that result from assessing the patient. Ruling out life-threatening diseases should be the first step in making a diagnosis. ECG and X-ray are the basic investigations for this approach. GRACE, HEART, and TIMI score are being used for acute coronary syndrome diagnosis and stratification. Among these, HEART scoring is considered the best for diagnosis (32). Similarly, each disease has its own diagnostic criteria, which are beyond the scope of this article.

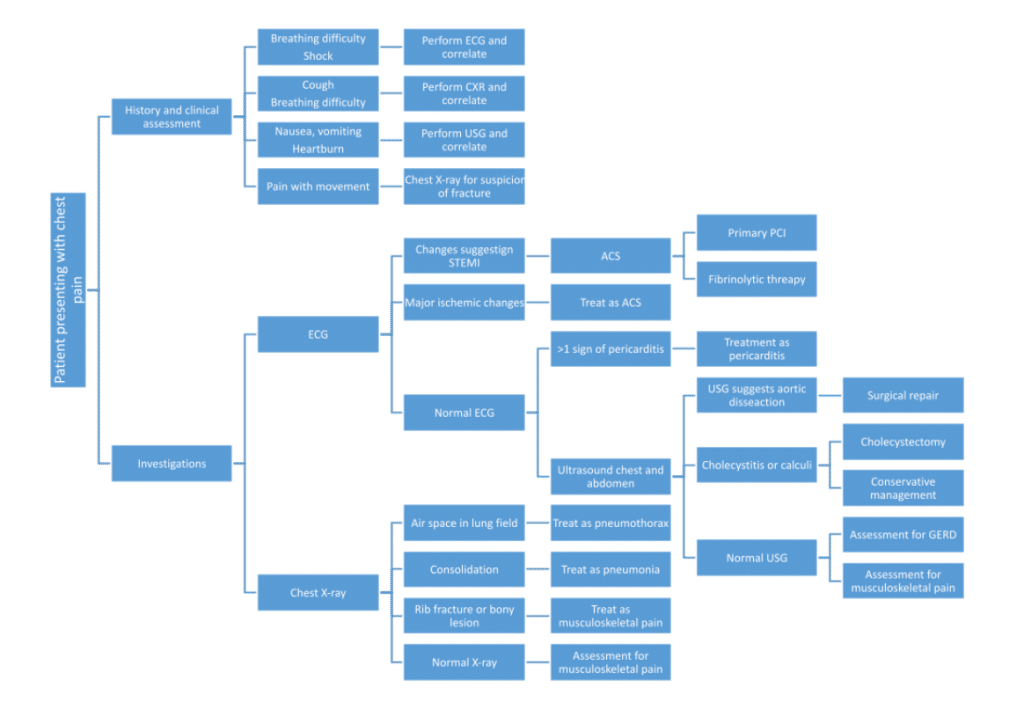

The basic approach and step-by-step management of a patient with chest pain can be made according to the following flow chart: (4, 11)

Treatment

It should be according to the final diagnosis made by the attending doctor. Each disease should be assessed and managed in its particular way. An overview of the treatment options is as follows:

Cardiovascular diseases

- Patients with the diagnosis of ACS and MI require immediate treatment. For ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), reperfusion therapy is the treatment of choice. It is done by PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) (33). If PCI is not available in the hospital, fibrinolytic therapy is the second best option, and the goal is to administer fibrinolytic agents within 30 minutes of first medical contact. These include tenecteplase, alteplase, and streptokinase (34). Aspirin and clopidogrel (antiplatelet therapy) are also administered with expected results of reduced myocardial infarction and recurrent ischemia, but the bleeding risk is calculated first. These are also helpful in non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). (33, 34)

- In the case of aortic dissection, open surgical repair, and thoracic endovascular aortic repair are recommended depending on the type of dissection (35).

- The treatment of pericarditis consists of anti-inflammatory drugs, including NSAIDs, corticosteroids, colchicine, IL-1 blockers, and antimicrobial therapy when indicated (36).

Respiratory diseases

- Pneumonia is usually treated with antibiotics and NSAIDs. Fluoroquinolones, macrolides, and beta-lactams can be used depending on the severity and resistance pattern. Oral medication is used for mild cases with nebulization. Intravenous medication is usually reserved for severe cases, and those patients admitted to the hospital (38).

- COPD and asthma are treated with corticosteroids (hydrocortisone), beta-agonists (salbutamol), and muscarinic antagonists (ipratropium). Emergency management includes intravenous corticosteroids and inhaled beta-agonists while maintenance therapy includes inhaled or oral beta agonists (both short-acting and long-acting), corticosteroids, and muscarinic antagonists with appropriate antibiotics in case of infection or exacerbation. COPD is a chronic disease, and life-long medication is recommended. (26, 27, 37)

- Tension Pneumothorax is an emergent condition, and immediate needle decompression is the recommended treatment with a thoracostomy tube placed above the rib in the 5th intercostal space anterior to the midaxillary line (28).

Gastrointestinal diseases

- GERD is usually treated symptomatically with antacids, H2-blockers, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), with the latter giving the best results. Surgery for GERD is fundoplication, but it is rarely done due to associated risks and low outcomes (39).

- Cholecystitis and gallbladder stones usually demand cholecystectomy, which is the best treatment option. Conservative treatment with antibiotics is also an alternative. For people who are not fit for surgery, percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD) can be done (29).

- In the case of Mallory-Weiss syndrome or esophageal tears, esophagogastroscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Other options are epinephrine local injection, endoscopic band ligation, and electrocoagulation. If not treated, Sengstaken-Blakemore tube compression is the last surgical option. PPIs and H2 blockers can be given for symptomatic treatment (20).

Musculoskeletal diseases

- Costochondritis can be treated with anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs with help from physiotherapy and immobilization of the patient. Muscle stretching is very important in relieving pain, but further support with trials is needed (40).

- Rheumatic diseases should be treated accordingly (painkillers, steroids, and immunosuppressant drugs for severe cases). Chiropractic care is also important in musculoskeletal chest pain and can prove to be cost-effective in most cases (41).

Complications of Causes of Chest Pain

- Complications usually develop if chest pain is associated with severe and life-threatening diseases like myocardial infarction, pericarditis, asthma, pneumothorax, and rheumatoid arthritis. MI can lead to arrhythmias, heart failure, and even death if no support is given. Cardiac tamponade is a rare complication of pericarditis and is associated with malignancy and infections (42).

- Pneumonia is usually a condition that resolves completely with medication, but sometimes complications develop. These can be lung fibrosis, cavitation, empyema, and pulmonary abscess (38).

- Pneumothorax-associated complications are respiratory failure, bronchopulmonary fistula, and cardiac arrest (28).

- Asthma and COPD can also cause respiratory dysfunction resulting in severe outcomes. While other diseases are mild to moderate in severity, and usually, no complication develops.

Prognosis

The prognosis also depends upon the causative disease.

- ACS has a good prognosis if treated properly and on time. However, there are chances of recurrence in patients who survived the first episode. Rehospitalization within 30 days usually occurs in one-sixth of cases. The prognosis after MI strongly depends on the ejection fraction of the heart (34).

- Pneumothorax is usually benign and resolves with treatment. However, chances of recurrence are present, almost 28% (28). Pneumothorax in HIV patients or patients with COPD is lethal and should be dealt with accordingly (28).

- COPD and asthma give good responses to appropriate therapy but long-term treatment is required.

- GERD is also treatable with medication but may worsen with age.

- Rheumatoid arthritis is a lifelong disease that requires proper management to remain symptom-free.

- Costochondritis is usually a self-limited disease (21).

Disclosures

The author does not report any conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes and is not intended to treat disease or supplant professional medical judgment. Physicians should follow local policy regarding the diagnosis and management of medical conditions.

See Also

Lower Urinary Tract Infections

Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

References

- Rui P, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 emergency department summary tables. National Center for Health Statistics. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf.

- Cayley WE Jr. Diagnosing the cause of chest pain. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Nov 15;72(10):2012-21. PMID: 16342831.

- Johnson K, Ghassemzadeh S. Chest Pain. 2022 Jul 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29262011.

- Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, Amsterdam E, Bhatt DL, Birtcher KK, Blankstein R, Boyd J, Bullock-Palmer RP, Conejo T, Diercks DB, Gentile F, Greenwood JP, Hess EP, Hollenberg SM, Jaber WA, Jneid H, Joglar JA, Morrow DA, O’Connor RE, Ross MA, Shaw LJ. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Nov 30;144(22):e368-e454. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001030. Epub 2021 Oct 28. PMID: 34709928.

- : Rui P, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2016 National Summary Tables. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2016_namcs_ web_tables.pdf.

- Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, Angelini K, Capewell S, Nicholl J. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart. 2005 Feb;91(2):229-30. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.027599. PMID: 15657244; PMCID: PMC1768669.

- Mehta PK, Bess C, Elias-Smale S, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi A, Pepine CJ, Bairey Merz CN. Gender in cardiovascular medicine: chest pain and coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2019 Dec 14;40(47):3819-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz784. PMID: 31713592; PMCID: PMC7963141.

- Ntritsos G, Franek J, Belbasis L, Christou MA, Markozannes G, Altman P, Fogel R, Sayre T, Ntzani EE, Evangelou E. Gender-specific estimates of COPD prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018 May 10;13:1507-1514. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S146390. PMID: 29785100; PMCID: PMC5953270.

- Fruergaard P, Launbjerg J, Hesse B, Jørgensen F, Petri A, Eiken P, Aggestrup S, Elsborg L, Mellemgaard K. The diagnoses of patients admitted with acute chest pain but without myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 1996 Jul;17(7):1028-34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014998. PMID: 8809520.

- Stochkendahl, M. J., & Christensen, H. W. (2010). Chest Pain in Focal Musculoskeletal Disorders. Medical Clinics of North America, 94(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2010.01.007

- Frcpe, M. B. I. P. D., Ffpm(Hon), F. F. F. M. S. R. H., Frcpe, M. B. M. S. W. J., & FRCPath, H. R. L. P. M. (2022). Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine (24th ed.). Elsevier.

- Barstow C, Rice M, McDivitt JD. Acute Coronary Syndrome: Diagnostic Evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Feb 1;95(3):170-177. PMID: 28145667.

- Smith JN, Negrelli JM, Manek MB, Hawes EM, Viera AJ. Diagnosis and management of acute coronary syndrome: an evidence-based update. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015 Mar-Apr;28(2):283-93. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140189. PMID: 25748771.

- Gawinecka J, Schönrath F, von Eckardstein A. Acute aortic dissection: pathogenesis, risk factors and diagnosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017 Aug 25;147:w14489. doi: 10.4414/smw.2017.14489. PMID: 28871571

- Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2015 Sep 12;386(9998):1097-108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60733-4. Epub 2015 Aug 12. PMID: 26277247; PMCID: PMC7173092.

- Rider AC, Frazee BW. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018 Nov;36(4):665-683. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2018.07.001. Epub 2018 Sep 6. PMID: 30296998; PMCID: PMC7126690.

- Jones TL, Neville DM, Chauhan AJ. Diagnosis and treatment of severe asthma: a phenotype-based approach. Clin Med (Lond). 2018 Apr 1;18(Suppl 2):s36-s40. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.18-2-s36. PMID: 29700091; PMCID: PMC6334025.

- Ko FW, Chan KP, Hui DS, Goddard JR, Shaw JG, Reid DW, Yang IA. Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. 2016 Oct;21(7):1152-65. doi: 10.1111/resp.12780. Epub 2016 Mar 30. PMID: 27028990; PMCID: PMC7169165.

- Young A, Kumar MA, Thota PN. GERD: A practical approach. Cleve Clin J Med. 2020 Apr;87(4):223-230. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.19114. PMID: 32238378.

- Rawla P, Devasahayam J. Mallory Weiss Syndrome. 2022 Oct 9. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 30855778.

- Schumann JA, Sood T, Parente JJ. Costochondritis. 2022 Jul 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 30422526.

- Freund Y, Chenevier-Gobeaux C, Bonnet P, Claessens YE, Allo JC, Doumenc B, Leumani F, Cosson C, Riou B, Ray P. High-sensitivity versus conventional troponin in the emergency department for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Crit Care. 2011 Jun 10;15(3):R147. doi: 10.1186/cc10270. PMID: 21663627; PMCID: PMC3219019.

- Sayed A, Munir M, Bahbah EI. Aortic Dissection: A Review of the Pathophysiology, Management and Prospective Advances. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2021;17(4):e230421186875. doi: 10.2174/1573403X16666201014142930. PMID: 33059568; PMCID: PMC8762162.

- Tchana-Sato V, Sakalihasan N, Defraigne JO. La dissection aortique [Aortic dissection]. Rev Med Liege. 2018 May;73(5-6):290-295. French. PMID: 29926568.

- Eshwara VK, Mukhopadhyay C, Rello J. Community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adults: An update. Indian J Med Res. 2020 Apr;151(4):287-302. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1678_19. PMID: 32461392; PMCID: PMC7371062.

- Agarwal AK, Raja A, Brown BD. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 32644707.

- Hashmi MF, Tariq M, Cataletto ME. Asthma. 2022 Aug 18. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 28613651.

- McKnight CL, Burns B. Pneumothorax. 2022 Nov 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 28722915.

- Pisano M, Allievi N, Gurusamy K, Borzellino G, Cimbanassi S, Boerna D, Coccolini F, Tufo A, Di Martino M, Leung J, Sartelli M, Ceresoli M, Maier RV, Poiasina E, De Angelis N, Magnone S, Fugazzola P, Paolillo C, Coimbra R, Di Saverio S, De Simone B, Weber DG, Sakakushev BE, Lucianetti A, Kirkpatrick AW, Fraga GP, Wani I, Biffl WL, Chiara O, Abu-Zidan F, Moore EE, Leppäniemi A, Kluger Y, Catena F, Ansaloni L. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Nov 5;15(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00336-x. PMID: 33153472; PMCID: PMC7643471.

- Gyawali CP, Kahrilas PJ, Savarino E, Zerbib F, Mion F, Smout AJPM, Vaezi M, Sifrim D, Fox MR, Vela MF, Tutuian R, Tack J, Bredenoord AJ, Pandolfino J, Roman S. Modern diagnosis of GERD: the Lyon Consensus. Gut. 2018 Jul;67(7):1351-1362. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314722. Epub 2018 Feb 3. PMID: 29437910; PMCID: PMC6031267.

- Winzenberg T, Jones G, Callisaya M. Musculoskeletal chest wall pain. Aust Fam Physician. 2015 Aug;44(8):540-4. PMID: 26510139.

- Poldervaart JM, Langedijk M, Backus BE, Dekker IMC, Six AJ, Doevendans PA, Hoes AW, Reitsma JB. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Jan 15;227:656-661. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.080. Epub 2016 Oct 30. PMID: 27810290.

- Bergmark BA, Mathenge N, Merlini PA, Lawrence-Wright MB, Giugliano RP. Acute coronary syndromes. Lancet. 2022 Apr 2;399(10332):1347-1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02391-6. PMID: 35367005; PMCID: PMC8970581.

- Switaj TL, Christensen SR, Brewer DM. Acute Coronary Syndrome: Current Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Feb 15;95(4):232-240. PMID: 28290631.

- Mussa FF, Horton JD, Moridzadeh R, Nicholson J, Trimarchi S, Eagle KA. Acute Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016 Aug 16;316(7):754-63. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10026. PMID: 27533160.

- Chiabrando JG, Bonaventura A, Vecchié A, Wohlford GF, Mauro AG, Jordan JH, Grizzard JD, Montecucco F, Berrocal DH, Brucato A, Imazio M, Abbate A. Management of Acute and Recurrent Pericarditis: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jan 7;75(1):76-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.021. PMID: 31918837.

- MacLeod M, Papi A, Contoli M, Beghé B, Celli BR, Wedzicha JA, Fabbri LM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation fundamentals: Diagnosis, treatment, prevention and disease impact. Respirology. 2021 Jun;26(6):532-551. doi: 10.1111/resp.14041. Epub 2021 Apr 24. PMID: 33893708.

- Sattar SBA, Sharma S. Bacterial Pneumonia. 2022 Aug 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 30020693.

- Clarrett DM, Hachem C. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Mo Med. 2018 May-Jun;115(3):214-218. PMID: 30228725; PMCID: PMC6140167.

- Zaruba RA, Wilson E. IMPAIRMENT BASED EXAMINATION AND TREATMENT OF COSTOCHONDRITIS: A CASE SERIES. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Jun;12(3):458-467. PMID: 28593100; PMCID: PMC5455195.

- Stochkendahl MJ, Sørensen J, Vach W, Christensen HW, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Hartvigsen J. Cost-effectiveness of chiropractic care versus self-management in patients with musculoskeletal chest pain. Open Heart. 2016 May 4;3(1):e000334. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000334. PMID: 27175285; PMCID: PMC4860847.

- Dababneh E, Siddique MS. Pericarditis. 2022 Aug 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 28613734.

- Singh A, Museedi AS, Grossman SA. Acute Coronary Syndrome. 2022 Jul 11. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29083796.

Follow us