Summary

Contents showLower urinary tract infection is a common infection of the lower urinary tract, most commonly occurring in female patients of reproductive age. Lower urinary tract infections is less common in male patients, and if present, it is generally associated with underlying risk factors.

The most common pathogen involved in urinary tract infections worldwide is Escherichia coli. The pathogenesis of lower urinary tract infections entails an ascending infection from the urethra due to local bacterial contamination in most cases.

The diagnosis of lower urinary tract infections comprises clinical evaluation and urinalysis. In suspicion of complications, several diagnostic methods are used to assess for differentials. The mainstay of treatment of lower urinary tract infections is antibiotic therapy.

Lower Urinary Tract Infections – Overview

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most common infections encountered in the outpatient department, especially in females. The incidence of urinary tract infections is 12% in females and 3% in males annually. Almost 60% of females are at risk of developing urinary tract infections at least once in their lifetime, making it a key morbidity. (1) The rise in antibiotic resistance is also a challenge in dealing with these infections and affects the overall outcome of disease and quality of life of the affected people. (2)

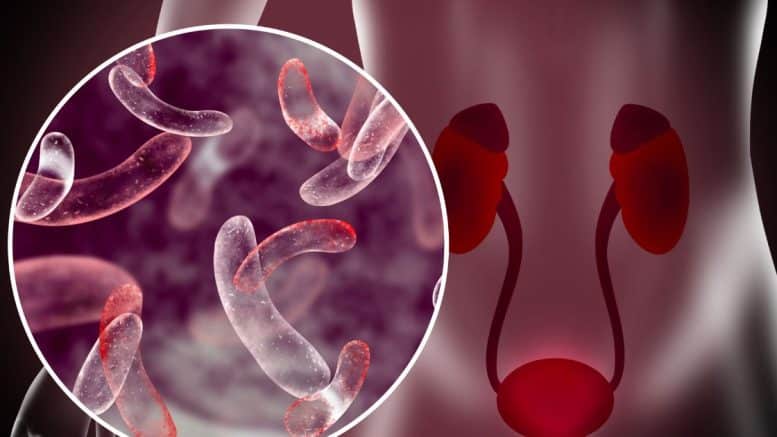

Anatomically, the urinary tract is divided into upper (kidney and ureter) and lower (urinary bladder and urethra) parts, with the disease classified accordingly as upper urinary tract infections and lower urinary tract infections. (3) In this article, we will focus on lower urinary tract infections, including acute urethritis and acute cystitis, with their symptoms, etiology, investigations, and treatment.

Definition of Lower Urinary Tract Infections

Uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection is an infection of the urinary tract confined to the urethra and bladder in females of reproductive age. It is usually not associated with any comorbid condition, such as diabetes, pregnancy, or any structural abnormality. (4) It usually has symptoms of cystitis and urethritis with pathogenic inflammation in the presence of significant bacteriuria. (5)

While the upper urinary tract infection involves the kidney and ureter causing pyelonephritis, and is usually associated with comorbidities such as structural abnormalities or diabetes. (4)

Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Infections

- Approximately 150 million people are affected by this disease worldwide annually, causing a burden on the healthcare system and budget (6). Lower urinary tract infections are more prevalent in females due to shorter urethra and absent prostatic secretions, which are bactericidal in nature (7).

- UTIs affect almost every other woman at least once during their life (making it 40%-60% of the total women population) and recurrent infections in every fourth woman (making it 20%-40%) (6, 8).

- In males, the incidence is much lower compared to females at almost 10%, with the number of cases increasing after the age of 65 years. UTIs in men are considered complicated in all cases. (5)

- There is also an increase in asymptomatic bacteriuria in elderly people leading to over-diagnosis and unnecessary antibiotics causing resistance. (9)

Etiology of Lower Urinary Tract Infections

The most common causative organism in uncomplicated or lower urinary tract infections is Escherichia coli (86%). This is followed by Klebsiella (5%), Proteus (3%), and S. saprophyticus (3%), with other species having minor contributions. (5, 10) The most important route is through the rectum (especially in females due to the close vicinity of the urethra), predisposing to UTIs. It is rarely caused by blood-borne bacteria. (4)

It is also discovered that the strains of Escherichia coli, which cause UTIs, are also found in retail meat, especially the ones obtained from poultry (chicken and turkey). They are considered a great reservoir and may be a potential source of transmission of E. coli. But the exact evidence proving retail meat consumption leads to UTIs is not yet established. (11)

One of the great risk factors for UTI is urethral catheterization. This may be done for any purpose (Input-Output record, C-section, urinary obstruction, kidney diseases). According to a study, almost 60% of cases of nosocomial urinary tract infections are due to the use of urinary catheters. (12)

Risk Factors for Lower Urinary Tract Infections

- Sexual intercourse;

- Use of spermicidal gels;

- Multiple partners;

- Urolithiasis;

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH);

- Bladder outflow obstruction;

- Fistula or vesicoureteral reflux;

- Uterine prolapse;

- Diabetes mellitus. (4, 7)

Pathophysiology of Lower Urinary Tract Infections

The main pillar of the pathophysiology of UTI is the infectious process by E. coli and other bacteria, as urine itself is a good medium for bacteria to grow. In females, short urethra, absent prostatic secretions, and close vicinity of the rectum lead to the easy ascent of bacteria. Furthermore, there are some receptors in the urothelium of the patient which provide the place for the attachment of bacteria causing the infection. (7)

The pathogenesis is unique for each pathogen. Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis utilize a similar method which includes motility of the organism, adherence to the receptors, production of toxic substances, and immune system evasion. Fimbria or flagella helps in the motility of the pathogen with the production of protein molecules that act as toxins. P. mirabilis also produces urease during the infectious process, while E. coli form intracellular communities of bacteria. The final result of the whole process depends on the immune response of the host, which determines the outcome. (13)

The preventive factors which control bacterial growth in this situation are an acidic medium with a pH of less than 5, high urea levels, a sufficient volume of urine, and frequent emptying of the bladder by voiding. (4)

Sexual activity can also increase the chances of UTI by causing minor abrasions, which can transfer bacteria from the perineum to the urethra and then ascend to the bladder. (7)

Clinical Features

The main clinical features of lower urinary tract infections include:

- Dysuria (burning micturition);

- Frequency (desire to pass urine frequently);

- Hesitancy (unable to initiate the urine stream);

- Tenesmus (Desire to pass more urine after voiding due to bladder wall spasm);

- Urgency (need to urinate urgently with no control);

- Cloudy and foul-smelling urine;

- Hematuria (blood in urine, either visible or microscopic) (4, 7).

The symptom of UTI having the highest clinical importance is dysuria. A patient presenting only with dysuria can raise the possibility of UTI up to 50%, while its combination with frequency can raise the suspicion to 90%. (14) Dysuria can also be present in vaginitis, but the absence of vaginal discharge or irritation can be used to rule out the disease. (15) The color and odor of the urine may also be present but should never be used alone as diagnostic because the sensitivity and specificity are low. Also, it depends upon the patient’s hydration status and the level of urea present in urine. (16)

UTIs in children present with pollakiuria (frequent daytime urination without any specific cause, also known as benign idiopathic urinary frequency), dysuria, and fever. Children less than 2 years of age present with non-specific signs and symptoms. Any child presenting with fever and having no definite source should be observed for UTI. (17)

The differentiation of upper and lower urinary tract infections is also important as both demand different kinds of treatment. It is usually done on the basis of clinical features. Pyelonephritis may present with the same symptoms but usually have fever with rigors and chills and loin tenderness. (17) On examination, the presence of costovertebral angle tenderness may suggest pyelonephritis. (15) The ESR test was considered to be helpful earlier, but the trials suggest no advantage. However, a consistently low CRP level may be helpful in ruling out pyelonephritis, but up till now, no recommendations for these laboratory tests have been present. (18)

Differential Diagnosis of Lower Urinary Tract Infections

The other diseases which must be ruled out before starting the treatment are different in men and women due to the presence of different anatomical structures, especially genitalia.

In men, it can be prostatitis or epididymitis, while in women, vaginitis, cervicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease should be ruled out. Other common conditions are syphilis, radiation or interstitial cystitis, renal stone, renal infarction, and painful bladder syndrome.

Diagnostic Criteria for Lower Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs are mostly diagnosed clinically with some help from laboratory investigations. Among signs and symptoms, dysuria is the best indicator, followed by frequency and urgency. This combination raises the suspicion of the disease up to 90%. (14) Further laboratory investigations can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Urine Sample Collection Methods

Before discussing the investigations, it is compulsory to talk about the techniques for urine collection both in children and adults to prevent contamination and obtain the best results.

Contamination of urine can be due to vaginal and perianal flora or epithelial cells of the skin. (19) The most widely accepted threshold for contamination is equal to or greater than 10,000 colony-forming units per mL (CFL/mL) when described in terms of colony-forming units per mL, with equal or greater than 2 isolates with it. (19)

Different methods are currently used for urine collection, having their own pros and cons. These include:

Suprapubic aspiration

It is the best method to obtain sterile urine without any contamination, but it may cause patient discomfort; it is a difficult method and invasive technique. So it is rarely used for an uncomplicated UTI.

Catheterization

The patient can be catheterized temporarily to obtain urine in an emergency and outpatient setting. It is easy but can cause the introduction of bacteria into the bladder. So it is used only when indicated.

Mid-stream Clean Catch Technique

It is the most commonly used technique. It can be used with or without cleansing. It is cost-effective, quick, and easy. But on the other hand, it may cause contamination leading to false positive results. (20) Urinary collection devices are also available for convenience, but no help in preventing contamination is observed. (21)

Techniques for Children

Non-invasive methods that can be employed to collect urine in non-toilet children are nappy pads, urinary bags, clean catch, and voiding stimulation techniques. Invasive techniques include urinary catheterization and the suprapubic method. (22)

By far, the catheterization method is the best one considering urine has no contamination (compared to the clean catch technique) and is easy and cost-effective. (23)

Investigations

Various investigations are available that help in UTI diagnosis. These are as follows:

Urinalysis with microscopy

It is the first and most important step. It can detect physical, chemical, and microscopic abnormalities in urine (if present). These include color and odor of urine, pH, turbidity, pyuria or RBCs, protein, and glucose in urine. It is also helpful in ruling out other diseases, which clears the vision in diagnosis. (4, 5, 7)

Leukocyte Esterase

It shows the presence of neutrophils in urine on a dipstick. These can be intact or broken down by enzymatic degradation. It has high sensitivity (62% to 98%) and specificity (55% to 96%). But it is mostly used in combination with nitrites dipstick as alone can have false positive results due to contamination of urine. (5, 7)

Nitrites

Some bacteria, usually gram-negative, convert nitrates to nitrites through reduction. These nitrites, when present in urine, are indicative of infection by these bacteria, as no nitrites are present in urine in normal conditions. This makes the nitrites dipstick test specific for UTI. Although false positive results may occur due to air exposure of specimen and false negative results due to low nitrate diet and non-nitrite bacteria. (5, 7) Together, nitrite and leukocyte esterase tests can predict UTI accurately up to 96%. (24)

Urine Culture

A urine culture may be important in recurrent infections, resistance to antibiotic treatment, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women. Otherwise, it is not recommended for uncomplicated UTIs. The diagnostic standard on urine culture is greater than 10⁵ colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL). (4) It is also helpful in prescribing the correct antibiotic and preventing antibiotic resistance. (5)

Multiplex PCR molecular testing

It is the most advanced approach to the detection of bacteria in UTIs. In this method, DNA extraction and analysis of the causative organism are done. Studies have shown that it is more accurate than urine culture and can detect bacteria in patients whose urine culture was negative. It is also more sensitive than urine culture in the detection of infection caused by multiple bacteria (polymicrobial). But its clinical importance has to be proven by other studies. That is why it is not recommended yet. (25)

Others

In children, full blood count, serum urea, and creatinine can be done as they present with non-specific symptoms, and there may be an associated disorder of the renal system. (7) Renal ultrasound and CT can be done to rule out pyelonephritis. Cystoscopy is also done in some cases. (4, 7)

Treatment for Lower Urinary Tract Infections

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are the recommended first line of treatment for UTI. Different classes of antibiotics are being used according to sensitivity and local resistance. These include:

- Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole: It is considered the first choice in antibiotics for UTI, but resistance is high. It should not be used if local resistance is higher than 20% (4, 5, 7). It is also nephrotoxic and should be used with a close eye on eGFR (7). The recommended dose is 160/80 mg two times a day for 3 days (26).

- Nitrofurantoin: It can also be used, but it is bacteriostatic, not bactericidal. That is why it is used for 5-7 days. The dose is 100 mg two times a day. (4, 5, 26)

- Amoxicillin and cephalosporins: This is the drug of choice in uncomplicated UTIs in children. Amoxicillin-clavulanate and second or third-generation cephalosporins can be used. For infants of less than 2 months of age, parenteral amoxicillin and gentamycin or third-generation cephalosporins are recommended. Intravenous medication is also useful in children who are hemodynamically unstable, have a toxic look, or are unable to tolerate oral feed (27). These are also safe in pregnancy, but resistance makes their use limited.

- Fosfomycin Trometamol: This is one of the most effective antibiotics for UTIs and is also safe in pregnancy. Three grams of Fosfomycin can be taken as a single dose antibiotic therapy with or without nitrofurantoin (26). It also has higher patient compliance. A single dose of Fosfomycin is considered to have the same efficacy as the other antibiotics, which have to be used for 3-5 days, making it a better choice by all means (28).

- Fluoroquinolones: Ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin are usually reserved for complicated UTIs. As most of the UTIs in men are considered to be complicated (as they include prostatitis and may involve pyelonephritis, too), it is usually preferred in males, having a good response and little resistance. But overuse should be avoided. (26)

Antibiotics are the gold standard for the treatment of UTI and are recommended in every case. There have been studies about non-antibiotic products (such as NSAIDs, D-mannose, vitamins, and estrogens) to replace antibiotics and prevent antibiotic resistance. But up till now, no other approach has been more effective than antibiotics (29). In elderly patients with UTI, there are results showing an increased number of bloodstream infections in case of no antibiotics used, with numbers decreasing in patients with early use of antibiotics (30). This shows the importance of antibiotics in the prognosis of UTIs.

Analgesics

NSAIDs and urinary analgesics such as phenazopyridine (200 mg thrice daily) may be used to provide relief from pain. These are important in the symptomatic satisfaction and comfort of the patient. A hot sit bath may also help in pain relief. (26)

Cranberry Juice and Capsules

Cranberry extract has been used for a long time in prophylaxis and also in the treatment of UTIs. It contains proanthocyanidins (PAC) which act as an anti-adhesive substance against E.coli and antibacterial against other causative organisms. The use of cranberry capsules has been shown to reduce the chances of UTIs in high-risk patients, while no advantage was given in low-risk patients (31). The use of cranberry capsules has also been shown to reduce the risk of UTI to half in females planning to have gynecological surgeries with urinary catheterizations (32).

Estrogens

Estrogens prescribed with antibiotic therapy can prevent UTIs, especially in postmenopausal women and in recurrent infections (33). It is prescribed as a vaginal ointment of 0.5 g applied at night time for two weeks and then two times a week (26).

Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract infections

Patient education and counseling are most important for the prevention of UTIs. Personal hygiene, adequate washing of hands and wiping after urination, using adult or baby wipes instead of toilet paper, washing the vaginal area first while defecating or in the shower, voiding after sexual intercourse, and frequent emptying of the bladder may be helpful in prevention, especially in patients with recurrent UTIs (5, 15). But the evidence of a decrease in incidence in low-risk patients is lacking.

Prophylactic antibiotics can also be used in recurrence in older patients to avoid complications, but further analysis is required to support this approach (34). Long-term antibiotics in children suffering from recurrent UTIs may reduce the incidence, but resistance may develop. (35)

Urinary catheterization may also predispose to bacterial invasion and should be avoided if possible and only done when indicated with proper prophylactic antibiotics. (5)

Complications of Lower Urinary Tract infections

Lower UTI, if not treated, may lead to other problems, including:

- Pyelonephritis;

- Obstructive pyelonephritis;

- Chronic prostatitis;

- Urinary calculi due to retention;

- Renal abscess;

- Focal renal nephronia;

- Sepsis;

- Prolonged antibiotic treatment may lead to antibiotic resistance.

Disclosures

The author does not report any conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes and is not intended to treat disease or supplant professional medical judgment. Physicians should follow local policy regarding the diagnosis and management of medical conditions.

See Also

Acute Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Approach to the Patient With Acute Vestibular Symptoms

References:

- Foxman, B. (2014). Urinary Tract Infection Syndromes. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 28(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.003

- Ching C, Schwartz L, Spencer JD, Becknell B. Innate immunity and urinary tract infection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020 Jul;35(7):1183-1192. doi: 10.1007/s00467-019-04269-9. Epub 2019 Jun 13. PMID: 31197473; PMCID: PMC6908784.

- Dobrek Ł. DRUG-RELATED URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS. Wiad Lek. 2021;74(7):1728-1736. PMID: 34459779.

- Bono MJ, Leslie SW, Reygaert WC. Urinary Tract Infection. 2022 Jun 15. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29261874.

- Lala V, Leslie SW, Minter DA. Acute Cystitis. 2022 Jul 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 29083726.

- Marcon, J., Stief, C. G., & Magistro, G. (2017). Harnwegsinfektionen. Der Internist, 58(12), 1242–1249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00108-017-0340-y

- Penman, I. D., Ralston, S. H., Strachan, M. W. J., & Hobson, R. (2022). Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. Elsevier Gezondheidszorg.

- Anger J, Lee U, Ackerman AL, Chou R, Chughtai B, Clemens JQ, Hickling D, Kapoor A, Kenton KS, Kaufman MR, Rondanina MA, Stapleton A, Stothers L, Chai TC. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2019 Aug;202(2):282-289. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000296. Epub 2019 Jul 8. Update in: J Urol. 2022 Oct;208(4):754-756. PMID: 31042112.

- Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman H, Goudie R, Molokhia M, Johnson AP, Holmes AH, Aylin P. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all cause mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019 Feb 27;364:l525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525. PMID: 30814048; PMCID: PMC6391656.

- Behzadi P, Behzadi E, Yazdanbod H, Aghapour R, Akbari Cheshmeh M, Salehian Omran D. A survey on urinary tract infections associated with the three most common uropathogenic bacteria. Maedica (Bucur). 2010 Apr;5(2):111-5. PMID: 21977133; PMCID: PMC3150015.

- Yamaji R, Friedman CR, Rubin J, Suh J, Thys E, McDermott P, Hung-Fan M, Riley LW. A Population-Based Surveillance Study of Shared Genotypes of Escherichia coli Isolates from Retail Meat and Suspected Cases of Urinary Tract Infections. mSphere. 2018 Aug 15;3(4):e00179-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00179-18. PMID: 30111626; PMCID: PMC6094058.

- Kranz J, Schmidt S, Wagenlehner F, Schneidewind L. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections in Adult Patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Feb 7;117(6):83-88. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0083. PMID: 32102727; PMCID: PMC7075456.

- Nielubowicz, G., Mobley, H. Host–pathogen interactions in urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol7, 430–441 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2010.101

- Bent S, Nallamothu BK, Simel DL, Fihn SD, Saint S. Does This Woman Have an Acute Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection? 2002;287(20):2701–2710. doi:10.1001/jama.287.20.2701

- Hooton, T. M. (2012). Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 366(11), 1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp1104429

- Schulz, L., Hoffman, R. J., Pothof, J., & Fox, B. (2016b). Top Ten Myths Regarding the Diagnosis and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 51(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.02.009

- Buettcher, M., Trueck, J., Niederer-Loher, A. et al.Swiss consensus recommendations on urinary tract infections in children. Eur J Pediatr 180, 663–674 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03714-4

- Shaikh N, Borrell JL, Evron J, Leeflang MM. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 20;1(1):CD009185. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009185.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Sep 10;9:CD009185. PMID: 25603480; PMCID: PMC7104675.

- Lough ME, Shradar E, Hsieh C, Hedlin H. Contamination in Adult Midstream Clean-Catch Urine Cultures in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Emerg Nurs. 2019 Sep;45(5):488-501. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2019.06.001. PMID: 31445626.

- Sinawe H, Casadesus D. Urine Culture. 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 32491501.

- Hayward G, Mort S, Yu LM, Voysey M, Glogowska M, Croxson C, Yang Y, Allen J, Cook J, Tearne S, Blakey N, Tonner S, Sharma V, Patil M, Kelly S, Butler CC. Urine collection devices to reduce contamination in urine samples for diagnosis of uncomplicated UTI: a single-blind randomised controlled trial in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2022 Feb 24;72(716):e225-e233. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2021.0359. PMID: 34990390; PMCID: PMC8803092.

- Kaufman J, Temple-Smith M, Sanci L. Urine sample collection from young pre-continent children: common methods and the new Quick-Wee technique. Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Dec 26;70(690):42-43. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X707705. PMID: 31879314; PMCID: PMC6919502.

- Altuntas N, Alan B. Midstream Clean-Catch Urine Culture Obtained by Stimulation Technique versus Catheter Specimen Urine Culture for Urinary Tract Infections in Newborns: A Paired Comparison of Urine Collection Methods. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29(4):326-331. doi: 10.1159/000504443. Epub 2019 Oct 31. PMID: 31665720; PMCID: PMC7445695.

- Richards KA, Cesario S, Best SL, Deeren SM, Bushman W, Safdar N. Reflex urine culture testing in an ambulatory urology clinic: Implications for antibiotic stewardship in urology. Int J Urol. 2019 Jan;26(1):69-74. doi: 10.1111/iju.13803. Epub 2018 Sep 16. PMID: 30221416.

- Wojno KJ, Baunoch D, Luke N, Opel M, Korman H, Kelly C, Jafri SMA, Keating P, Hazelton D, Hindu S, Makhloouf B, Wenzler D, Sabry M, Burks F, Penaranda M, Smith DE, Korman A, Sirls L. Multiplex PCR Based Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Analysis Compared to Traditional Urine Culture in Identifying Significant Pathogens in Symptomatic Patients. Urology. 2020 Feb;136:119-126. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.10.018. Epub 2019 Nov 9. PMID: 31715272.

- Papadakis, M., McPhee, S., Rabow, M., & McQuaid, K. (2022b). CURRENT Medical Diagnosis and Treatment 2023 (Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment)(62nd ed.). McGraw Hill / Medical.

- Leung AKC, Wong AHC, Leung AAM, Hon KL. Urinary Tract Infection in Children. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019;13(1):2-18. doi: 10.2174/1872213X13666181228154940. PMID: 30592257; PMCID: PMC6751349.

- Wang T, Wu G, Wang J, Cui Y, Ma J, Zhu Z, Qiu J, Wu J. Comparison of single-dose fosfomycin tromethamine and other antibiotics for lower uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Jul;56(1):106018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106018. Epub 2020 May 15. PMID: 32417205.

- Wawrysiuk S, Naber K, Rechberger T, Miotla P. Prevention and treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance-non-antibiotic approaches: a systemic review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019 Oct;300(4):821-828. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05256-z. Epub 2019 Jul 26. PMID: 31350663; PMCID: PMC6759629.

- Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman H, Goudie R, Molokhia M, Johnson AP, Holmes AH, Aylin P. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all cause mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2019 Feb 27;364:l525. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l525. PMID: 30814048; PMCID: PMC6391656.

- Caljouw MA, van den Hout WB, Putter H, Achterberg WP, Cools HJ, Gussekloo J. Effectiveness of cranberry capsules to prevent urinary tract infections in vulnerable older persons: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial in long-term care facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Jan;62(1):103-10. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12593. PMID: 25180378; PMCID: PMC4233974.

- Foxman B, Cronenwett AE, Spino C, Berger MB, Morgan DM. Cranberry juice capsules and urinary tract infection after surgery: results of a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Aug;213(2):194.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.04.003. Epub 2015 Apr 13. PMID: 25882919; PMCID: PMC4519382.

- Ferrante KL, Wasenda EJ, Jung CE, Adams-Piper ER, Lukacz ES. Vaginal Estrogen for the Prevention of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021 Feb 1;27(2):112-117. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000749. PMID: 31232721.

- Ahmed H, Farewell D, Jones HM, Francis NA, Paranjothy S, Butler CC. Antibiotic prophylaxis and clinical outcomes among older adults with recurrent urinary tract infection: cohort study. Age Ageing. 2019 Mar 1;48(2):228-234. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy146. PMID: 30165433; PMCID: PMC6424374.

- Williams G, Craig JC. Long-term antibiotics for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Apr 1;4(4):CD001534. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001534.pub4. PMID: 30932167; PMCID: PMC6442022.

Follow us