Summary

Contents showAcute headache is a common presentation among patients consulting primary care or emergency departments.

Acute headaches are classified according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders. The main feature for classification is the presence of an underlying etiology, which differentiates primary (non-identifiable etiology) from secondary (identifiable etiology) headache disorders.

The diagnosis and management of acute headaches rely on clinical presentation, suspicion of secondary life-threatening causes of acute headache, physical examination (particularly neurological exam), and complementary studies when indicated.

Introduction to Acute Headache in Adults

Acute headache in adults is one of the most frequent clinical concerns among patients presenting to emergency departments and a common pathology treated by neurologists and general practitioners. Headache disorders differ in various aspects and are relevant to appraise since they could be the cardinal symptom of a life-threatening underlying condition. Fortunately, most patients with headaches are safely discharged home after a complete medical evaluation. (1)

This article explains the syndrome and its most common causes and offers an overview of the essential aspects of managing headache disorders in the acute setting.

Definition of Headache

Headache is a symptom that involves the sensation of pain in the cephalic region of the body. The syndromes differ in presentation among patients, but most of the syndromes correlate with a particular pattern of clinical presentation.

Classification of Headaches

The International Association of Headaches Disorders classifies headache disorders according to their clinical characteristics, diagnostic results, the evolution of the syndrome, the response to treatment, and genetics, in some cases. (2) (Figure 1) It is not always necessary to know the complete classification. For the primary/acute care settings, levels 2 and 3 of the hierarchy should be enough. Deeper levels generally aim at long-term care and research purposes. (2)

Example: A 50-year-old man visits the emergency department concerned with an acute, severe, rapidly progressing, holocephalic headache. He has no history of trauma. Medical history is positive for hypertension and smoking. The ED physician orders a head CT without contrast and yields a subarachnoid hemorrhage pattern.

This example’s classification is Secondary headache > Cranial or cervical vascular disease > Non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The main two categories of differentiation are primary and secondary headaches. The former are processes for which the underlying cause is not yet known. The latter involves an underlying condition that triggers pathophysiological processes for pain production. (3)

Figure 1. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) (simplified version) (2)

Part 1: The Primary Headaches

- Migraine

- Tension-type headache

- Trigeminal autonomic cephalgia

- Other primary headache disorders

Part 2: The Secondary Headaches—Headache (or Facial Pain) Attributed to:

- Trauma or injury to the head and/or neck

- Cranial or cervical vascular disease

- Nonvascular intracranial disorder

- A substance or its withdrawal

- Infection

- Disorder of homeostasis

- Disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cervical structure

- Psychiatric disorder

Part 3: Painful Cranial Neuropathies, Other Facial Pains, and Other Headaches

- Painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pain

- Other headache disorders

Appendix

For a complete version, please visit the following complementary material.

ICHD-3

Epidemiology of Headaches

Headache is one of the most common concerns in emergency department patients, accounting for 3% of annual visits. (4) Over the three months evaluated in the same study, 15.3% of patients reported severe headaches, from which 20.7% were females, and 9.7% were males, configuring a female/male ratio of 2.13. Primary Headaches are frequent in women in the range of 20-40 years old. (5)

Primary headaches are more frequent than secondary headaches. Among them, tension-type headache is the most prevalent one. (6)

Headache produces a significant decrease in patients’ overall quality of life. (7)

Estimating the general annual economic burden only in patients with migraines in the United States results in approximately $78 billion. (8)

Approach to the Patient with Acute Headache

Key points:

- Follow the ABCDE approach to every primary care/ED patient.

- Have complete documentation of vital signs.

- Take a focused history. When possible, do it systemically, too.

- Focus on the diagnosis of life-threatening causes of secondary headaches.

- Decide the appropriate disposition.

On the first encounter with a patient concerned with a headache, one should characterize the type of pain present. (9)

History: ask for personal and family history of headaches.

Evolution: time from the start, intermittent nature, history of previous episodes.

Characteristics of headache: may be dull, pulsatile, sharp, itchy, stabbing, or pressure-like.

Initial Circumstances: during sleep, after physical exertion, related to head trauma, after a procedure (angiography, craniotomy, endovascular procedure).

Localization and irradiation: could be unilateral, bilateral, frontal, nuchal, or facial. The pattern of irradiation is also of interest if present.

Aggravating factors: head-position change, aggravated with light exposure or high-intensity sounds.

Accompanying signs and symptoms: nausea, vomiting, decreased level of consciousness, focal neurological deficit, dizziness, vertigo, fever, nuchal rigidity, pupillary changes, papilledema, signs and symptoms of infectious disease.

The intensity of pain: one can use visual analog scales or score from a range of numbers. It is also helpful to know the intensity relationship to previous episodes, if applicable.

Assess the red flags for secondary headaches. (Figure 2) This tool has been analyzed step by step by Thien Phu Do et al. and yielded high sensitivity and relatively low specificity for secondary headaches. (10)

Figure 2. Red flags for secondary headache. (10)

1- Systemic symptoms, including fever.

2- Neoplasm history.

3- Neurologic deficit (including altered level of consciousness).

4- Sudden or abrupt onset.

5- Older age (onset after 65 years).

6- Pattern change or recent onset of new headache.

7- Positional headache.

8- Precipitated by sneezing, coughing, or exercise.

9- Papilledema.

10- Progressive headache and atypical presentations.

11- Pregnancy or puerperium.

12- Painful eye with autonomic features.

13- Posttraumatic onset of headache.

14- Pathology of the immune system, such as HIV.

15- Painkiller overuse or new drug at onset of headache.

It is essential to assess the temporal relationship with symptoms and the number of episodes in the past, if present.

One should review comorbidities, allergies, toxins or substance use, current medications, and family history.

Vital signs are relevant, as in any emergency department patient, since an alteration may suggest an underlying life-threatening condition.

One should perform a complete neurological examination to look for findings that suggest a secondary cause or a primary one associated with a neurological deficit.

Further, provide a revision of systems not only in interrogation but also in the examination to assess comorbidities and look for clues of the underlying conditions according to clinical suspicion. Such findings include nuchal rigidity, papilledema, positive otoscopic results, adenopathy, and signs and symptoms of chronic diseases.

One of the primary purposes of critically evaluating patients with headaches is relieving pain and assessing for secondary causes. Moreover, properly instruct patients for whom a primary headache diagnosis is probable and would benefit from a specialized neurological assessment. (2, 3)

Etiology of Acute Headaches

As mentioned, primary headaches do not have an identifiable underlying cause.

If an underlying condition explains the syndrome, it should probably be classified as secondary.

A study performed by Munoz-Ceron et al. evaluated patients with non-traumatic headaches in the emergency department for seven weeks. (Table 1) The frequency of primary vs. secondary headaches was 59.4% vs. 25.9%. (11)

Table 1. The proportion of patients with secondary headache diagnosis. (11)

| 6. Cranial or cervical vascular disease | 15% |

| 7. Nonvascular intracranial disorder | 12.5% |

| 8. A substance or its withdrawal | - |

| 9. Infection | 22.5% |

| 10. Disorder of homeostasis | 15% |

| 11. Disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cervical structure | 32.5% |

| 12. Psychiatric disorder | 2.5% |

On the other hand, the HUNT study evaluated the onset of headache after trauma via surveys that showed to have ~85% of sensitivity and specificity compared to a personal interview with a neurologist as the gold standard. (12) The study found that 8.9% of the subjects developed headaches after a head injury. This study did not include the category of severe traumatic brain injury patients. A prospective study evaluating traumatic brain injury-related headaches showed that 10-38% of patients’ posttraumatic headaches were consistent with primary headache disorders. (13)

Presentation and Pathophysiological Implications of Acute Headaches

This section reviews the most common primary and secondary headaches presentations and briefly explains the underlying pathophysiology. One can read through each of them or study the one(s) of interest.

Primary Headaches:

Tension-Type Headache: (2, 3, 6, 14-19)

This headache usually presents as mild-moderate intensity pain, localized bilaterally. It is often dull, tight, or pressure-like. The evolution of pain is progressive, with a range of 30 minutes to 7 days in duration. Systemic features do not classically accompany tension-type headaches.

Several mechanisms account for the pathophysiology of tension-type headaches. Pericranial tenderness activates nociceptors in the pericranial fascia, muscle-tendon insertions, and muscles’ perivascular receptors, which have been implicated in the production of pain. A taut band of striated muscle, a localized muscle contraction, account for the myofascial trigger point hypothesis. Central mechanisms involved in the sensitization to pain and genetic factors seem to play a role in chronic forms of this type of headache. Environmental factors are thought to play a role in exacerbating headache episodes.

Migraine Headache: (2, 3, 18, 20, 21)

Migraine is usually a pulsatile, unilateral headache that lasts 4-72 hours. The intensity of pain may vary but is most commonly moderate to severe. Physical exertion, exposure to light, or high-intensity sounds may worsen the pain. Other features such as nausea, vomiting, and sensory symptoms may also be present. Migraine with aura is a syndrome in which transient neurological symptoms precede the headache. Other patients rarely present with hemiparesis, vertigo, or unilateral vision loss. Aura symptoms may last between 5-60 minutes, and visual auras are the most common.

Recent studies show that migraine headaches are associated with specific genetic patterns, and episodes develop due to homeostatic changes in the brain. In the premonitory phase, hypothalamic and limbic structures are involved, accounting for weakness, cravings, mood changes, or photophobia. Increased parasympathetic activity may activate meningeal nociceptors or modulate nociceptive signals from the trigeminal nucleus caudalis to structures involved in pain processing. Auras are thought to be produced by cortical spreading depression, which consists of increased depolarization followed by depression of cortical activity. The trigeminovascular pathway then involves the production of pain referred to as the V1 dermatome or the occipital region because of its connection with the cervical plexus.

Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias: (2, 3, 22, 23)

This group comprises acute unilateral headaches localized in the trigeminal distribution that are sudden in onset and high in intensity. Cluster headache is the most common of these, producing bouts of pain during periods of months, with consequent time free of pain after that. The attacks last minutes to hours and are accompanied by autonomic features such as conjunctival injection, rhinorrhea, ipsilateral flushing, lacrimation, and Horner syndrome.

The evidence points to hypothalamic dysfunction involving reflexes in the trigeminovascular, trigeminoautonomic, and trigeminocervical pathways that are believed to produce pain and the accompanying autonomic features.

Secondary Headaches:

This section explains common and life-threatening conditions to open the spectrum of differentials when a secondary cause is suspected. We will explain each disorder in detail in separate articles.

Trauma or injury to the head and/or neck: (2, 24, 25)

The ICHD-3 differentiates three entities: traumatic brain injury, whiplash injury, and craniotomy. The most crucial historical finding is a trauma to the head and neck before the initiation of the headache. Still, it is vital to look for clues for head injury when patients cannot communicate by themselves. Headache associated with trauma is usually unspecific and may mimic primary headache presentation. Risk factors for intracranial pathology include the mechanism of trauma, advanced age, alcohol-related disorders, and the use of antiplatelets or anticoagulants. Altered mental status, papilledema, or neurological deficit may indicate an underlying intracranial condition.

The literature depicts that inflammation may be essential in activating peripheral and central pathways to produce pain. Nociceptors in the scalp would account for the former and the action of microglia and oxidative stress for the latter. These mechanisms seem to overlap with the activation of the trigeminovascular pathway, which accounts for the non-specifical presentation of this clinical syndrome.

Cranial or cervical vascular disease:

This group of conditions includes non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage, unruptured vascular malformation, arteritis, cerebral ischemia/infarction, cerebral venous thrombosis, and cranial arterial dissection. Patients may present with a new-onset rapidly progressive severe headache, also called “thunderclap” headache, but may present with overlapping episodes of milder forms of unspecific headache. (2)

Cerebral ischemia or cerebral infarction rarely presents with headaches. These pathologies should be suspected in a patient with a new-onset headache and associated neurological deficit or a recent history of it (transient ischemic attack). The headache may mimic primary headaches and is usually self-limited. Patients may have cardiovascular risk factors for stroke, such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, auricular fibrillation, etc. (2, 26, 27)

The underlying mechanism could involve increased intracranial pressure due to cerebral edema or hemorrhagic transformation. The signals integrate with somatosensory and pain processing regions and modify the trigeminovascular system. (26, 27)

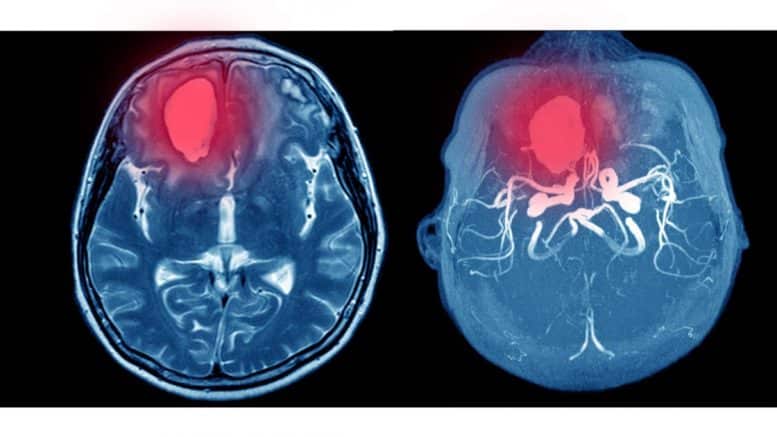

Non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage includes non-traumatic types of subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subdural hematoma. (2)

Intraparenchymatous hemorrhage (IPH), the deadliest type of stroke, is commonly presented along with an acute, moderate to high-intensity headache. Patients may present with a history of uncontrolled hypertension, anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug use, previous cerebral infarction, coagulopathy, vasculitis, substance abuse, especially cocaine and alcohol, and smoking. Patients with IPH may be young patients with uncontrolled hypertension, a history of vascular malformations, or elderly patients with coagulopathy, a group in which amyloid angiopathy is common. Important features to assess are decreased level of consciousness, airway compromise, uncontrolled hypertension, coagulopathy, neurological deficit, and previous underlying condition (cerebral infarction, vascular malformations, cerebral tumors). Although these patients may have florid presentations, they could also present oligosymptomatic. (2, 28, 29, 30)

Aneurysmatic subarachnoid headache (SAH) is one of the most concerning differentials. It should be suspected in young or mid-aged patients with a family or personal history of aneurysms, previous aneurysms, or smoking, one of the most common well-known risk factors for aneurysmal formation and progression. Patients could present with alterations in the level of consciousness, meningeal signs, neck stiffness, and neurological deficits. Further, there have been reported cases of milder forms of pain and no neurological findings. Clinical suspicion takes the lead when considering this differential, especially in non-typical cases. (2, 31-33)

Non-traumatic Subdural Hemorrhage (SDH), another life-threatening medical condition, may also present as a rapidly progressing severe headache and is usually followed by decreased level of consciousness, focal neurological signs, and may develop cerebral herniation syndromes. (2, 34)

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) usually occurs in mid-aged women with risk factors for thrombosis, such as estrogen therapy, obesity, smoking, prolonged bed rest, prior surgery, or head and neck infections. CVT may present with moderate to severe acute or subacute headaches. Neurological deficits, papilledema, alteration in level of consciousness, nausea, and vomiting may accompany the symptom. Slightly elevated body temperature is another concomitant finding, as in many thrombotic events. Fever could account for any head and neck infections associated with the development of CVT. (2, 32, 35, 36)

Intracranial Arterial Dissection (ICAD) is a rare condition, mostly in mid-aged or elderly patients. It may be associated with neck mobilization and cardiovascular risk factors for atherosclerosis, which may play a role in pathological changes in arterial walls and the production of dissection. Increased blood pressure is a common finding in patients with arterial dissection. Neurological deficits may accompany the syndrome with anterior (carotid artery dissection) or posterior (vertebral artery dissection) circulation signs and symptoms. The pain is usually acute and severe, localized to the neck, and maybe pulsatile or throbbing, irradiating to the cephalic or thoracic region. Signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure may be present in a secondary cerebral infarction setting. (2, 37, 38)

Unruptured cerebral arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are rare causes of headaches. Patients are typically young and refer to pressure-like or “heavy” type of headache, localizing the pain to the site of the AVM in some cases. Headaches associated with AVM can present characteristics like migraine, mainly if they localize in the occipital lobe. (39)

Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) is a large-vessel vasculitis characterized by granulomatous inflammation of large vessels. It usually presents in patients >50 years old and is associated with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR). Patients may present with unilateral headache, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, and associated systemic symptoms of PMR. Complications include stroke, visual disturbances, or vision loss. (2, 41, 42)

In vascular pathology, pain may originate from the irritation of the vasa nervorum due to inflammation, the release of reactive oxygen species, and pain-mediating neuropeptides. In the case of aneurysmal SAH, microvascular damage that leads to cerebral vasospasm plays a role in the production of pain and the lethal complications of this entity. (40)

Nonvascular intracranial disorder:

Under this group, increased intracranial pressure due to idiopathic intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, cerebral tumors, low CSF pressure, non-infectious inflammatory intracranial disease, and Chiari malformation type 1, are enumerated. (2)

Patients with increased intracranial pressure (ICP) are usually concerned with a non-specific type of headache, progressively worsening in evolution, which is usually worst in the morning when ICP is higher. Patients refer that the headache exacerbates when inclining the head forward and downward. Nausea, vomiting, altered mental status, cranial nerve six palsy, and neurological deficits associated with expanding mass lesions could be present. (32, 43, 44)

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (IIH) patients may present with tension-type headaches and increased intracranial pressure features, such as papilledema, decreased or loss of vision, and false localizing cranial nerve six palsies. This group usually comprises women of childbearing age and associated obesity. (43)

On the other hand, low ICP headaches, such as post-lumbar puncture headaches, usually worsen in sitting or standing positions and improve when lying down. The history of previous lumbar puncture is useful to suspect the diagnosis. Low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results in the traction of neural structures, leading to headaches. (2, 45, 46) When no clear relation to a previous lumbar puncture, a CSF fistula is a possible differential diagnosis. (2)

A substance or its withdrawal: (2)

Many substances are known to produce headaches when used. Nitrates, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, alcohol, cocaine, histamine, calcitonin-related peptide, vasopressors, and carbon monoxide are known to develop headaches. When evaluating patients complaining of a headache, it is paramount to assess the review of medications and domestic exposure to toxic substances.

Overusing medications such as NSAIDs, opioids, and ergotamine derivatives could cause headaches, especially in patients with chronic headache disorders.

Withdrawal of substances like caffeine, opioids, or estrogen, are known possible causes of new-onset headaches.

Infection: (2, 47, 48)

The most concerning infectious cause of headaches is acute meningitis. This life-threatening condition involves irritation and inflammation of the meninges due to locally spreading infection from the respiratory sinus or secondary to acute ear and mastoid process infections. In less than half of the presentations, patients present with the classic triad of headache, fever, and neck stiffness. Moreover, evolution may be subtle, including non-specific symptoms such as asthenia, altered level of consciousness, petechial rash, nausea, and vomiting. As in most infectious diseases, clinical history and epidemiological evaluation are relevant. Medical history of prior respiratory tract infection, ear infection, cranial surgery, or contact with meningitis cases should be investigated.

A cerebral abscess associated or not with meningoencephalitis should be suspected in the patient with headache and clinical features of infectious disease. Associated headaches may be of high intensity or subtle.

In another group of patients, other infections such as respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, and dermatologic infections could also cause headaches. One should evaluate patients according to their clinical context.

Disorder of homeostasis: (2, 49, 50)

Disorders of homeostasis include headaches due to high altitude, hypercapnia, or hypoxia, such as in high-altitude sickness, diving, or sleep apnea. Headaches due to dialysis can also occur.

Hypertension may cause headaches and should be a concern in severely elevated blood pressure (Hypertensive crises) or in a pregnant or puerperal woman, making pre-eclampsia a pathology of significant relevance.

Headaches attributed to hypothyroidism or fasting are also described.

A complete clinical history, vital signs, and physical examination are of paramount importance to suspect these differential diagnoses.

Acute glaucoma: (32, 62)

An acute glaucoma is a form of “red eye” presentation. Patients are usually concerned with intense acute ocular pain with intraocular irradiation, nausea, vomiting, and lacrimation. Symptoms are classically accompanied by central conjunctival injection, mydriasis, cloudy cornea, and petrous eye to palpation.

Diagnosis and Management of Acute Headaches in Adults

A diagnostic workup and appropriate measurements are warranted when a secondary headache is suspected. This section offers an outlined version of the diagnosis and management approach to secondary headaches’ most common and life-threatening causes. Practice essentials for common primary headaches are also outlined. Detailed information about diagnosing and managing primary and secondary headaches will be presented in separate articles.

Secondary Causes of Acute Headaches in Adults

Traumatic Brain Injury: (51, 52)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform a focused neurological assessment, examination of the head and neck, and fundoscopy.

- Classify patients according to GCS.

- Head elevation to 30º (Provided proper neck stabilization if indicated).

- Brain CT if moderate or severe head trauma. Indicated in high-risk mild TBI as well.

- Antiseizure medications if concomitant seizures.

- Anti-edema measurements if indicated.

- Neurosurgical consultation if intracranial pathology is confirmed or highly suspected (diffuse axonal injury).

- Disposition:

- Severe and moderate TBI: ICU or Neuro ICU.

- Mild TBI without brain CT findings may benefit from observation in the ED and discharge if no new anamnesis or physical exam changes.

Ischemic Stroke: (53)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform a focused neurological assessment, examination of the head and neck, and fundoscopy.

- NIH Stroke Score.

- Evaluate criteria for fibrinolysis.

- Maintain proper homeostatic measurements (O2, blood glucose, BP, etc.).

- Urgent head CT without contrast. Brain MRI or CTA should not delay fibrinolysis if indicated.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, Blood Gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- Neurological consultation.

- Disposition: ICU or Stroke unit.

Intraparenchymatous Hemorrhage: (54)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform a focused neurological assessment and fundoscopy.

- Head elevation to 30º if suspected or confirmed cerebral edema.

- Urgent head CT without contrast.

- Cautiously lower BP to SBP <150mmHg.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, Blood Gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- Antiedema measurements if needed.

- Neurosurgical consultation.

- Disposition: ICU or Neuro ICU. Possible neurosurgical intervention.

Non-traumatic SDH: (34, 55)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Focused neurological assessment, fundoscopy.

- Head elevation to 30º if suspected or confirmed cerebral edema.

- Urgent head CT without contrast.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, Blood Gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- Antiedema measurements if needed.

- Urgent Neurosurgical consultation.

- Disposition: ICU or Neuro ICU. Possible neurosurgical intervention.

Non-traumatic SAH: (31-33, 56-59)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform a focused neurological assessment, examination of the head and neck, and fundoscopy.

- Head elevation to 30º if suspected or confirmed cerebral edema. Bed rest.

- Apply the Ottawa rule for SAH in an adult patient with new-onset thunderclap headache, no neurological deficit, no history of aneurysms, brain tumors, or headache disorder. (Figure 3)

- Urgent head CT without contrast. ~98% sensitivity and ~99% specificity in the first six hours.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, Blood Gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- If there are no contraindications, perform a lumbar puncture when negative CT scan since there are cases of minimal SAH. Head CT is not reliable in detecting spinal SAH. CSF culture if suspicion of meningoencephalitis.

- Neurosurgical consultation.

- Antiedema measurements if indicated.

- Goal MAP >90mmHg (SBP <160mmHg)

- Nimodipine 60mg/4 hours PO.

- Disposition: ICU or Neuro ICU.

Figure 3. The Ottawa SAH rules: (56)

- Age > or equal to 40.

- Neck pain or stiffness.

- Witnessed loss of consciousness.

- Onset during exertion.

- “Thunderclap headache” (instantly peaking pain)

- Limited neck flexion on examination.

Inclusion criteria: age equal to or more than 15 years old. New, severe nontraumatic headache. Maximum intensity within 1 hour.

Exclusion criteria: a new neurologic deficit. Previous aneurysm. Known brain tumor. History of recent headaches.

~100% sensitivity and ~37% specificity for SAH. (60)

Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis: (32, 35, 36)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform a focused neurological assessment, examination of the head and neck, and fundoscopy.

- Head elevation to 30º if suspected or confirmed cerebral edema.

- Head CT without contrast has poor sensitivity for CVT. Perform MRI and MRI venography if CVT is suspected.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, blood gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- Neurological consultation.

- Disposition: ICU or Neuro ICU.

Brain tumor: (32, 44)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment and fundoscopy.

- Head CT with and without contrast.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, blood gases and electrolytes, and coagulation panel.

- Neurosurgical consultation.

- Disposition may depend on the type of tumor and the patient’s clinical status.

Intracranial arterial dissection: (37, 38)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment and fundoscopy.

- Head CT angiography. Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) if indicated.

- EKG.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, blood gases and electrolytes, coagulation panel, and cardiac troponin.

- Neurosurgical or neurointerventionism team consultation.

- Disposition: ICU or Neuro ICU.

Meningoencephalitis: (32, 47)

- Adopt proper PPE when meningitis is suspected.

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment and fundoscopy.

- Installing intravenous antibiotic therapy is the priority.

- Assess for sepsis criteria.

- Head CT without contrast to rule out increased ICP surrogates.

- LP with cultures if no contraindications.

- Order labs including CBC, metabolic panel, blood gases and electrolytes, liver enzymes, and coagulation panel.

- Infectious Disease specialist consultation.

- Disposition: ICU.

Hypertensive crises: systolic BP ≥180mmHg, and diastolic BP ≥120mmHg. (49, 50)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment and fundoscopy.

- Assessment for target organ damage:

- EKG, cardiac troponins: myocardial ischemia/infarction.

- Chest X-ray: pulmonary edema or congestion

- CBC, BMP, Urinalysis, ABG: Acute kidney injury, microangiopathic anemia.

- Head CT/MRI: hypertensive encephalopathy or other complications (ICH, Stroke, arterial dissections).

- Cautiously lower BP according to diagnostic results.

- Cardiological and Neurological consultation.

- Disposition: Coronary Unit/ICU if a hypertensive emergency. Observation/discharge if hypertensive urgency.

Giant Cell Arteritis: (41, 42)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment, fundoscopy, and head and neck palpation.

- Order labs including CRP, ESR, CBC, metabolic panel, Blood Gases and electrolytes, and coagulation panel.

- Doppler Ultrasound of extracranial vessels.

- If there is high clinical suspicion or positive diagnostic results, start Prednisone at 1mg/kg/day.

- Ophthalmology and Neurology consultation.

- Disposition: if no complications are detected and good clinical status, discharge. Inpatient treatment if complications are detected.

Acute Glaucoma: (32, 62)

- ABCDE approach and stabilization.

- Perform focused neurological assessment, eye palpation, fundoscopy.

- Ask the patient to lie on their back

- NSAIDs for pain management.

- Acetazolamide 500mg PO or IV.

- Topical beta blockers, alpha agonist or prostaglandin analogs.

- Urgent Ophthalmologic consultation.

Primary Causes of Acute Headaches in Adults

After an initial complete assessment of patients with potential primary headaches, pain management is next. Note that the diagnostic criteria for primary headaches rely on clinical presentation. (2) Diagnosis of primary headache most commonly corresponds to the so-called “green flags.” (Figure 4) (61)

Figure 4. Criteria for Low-Risk Headaches: (61)

- Age younger than 30 years

- Features typical of primary headaches (Tables 1 through 5)

- History of similar headache

- No abnormal neurologic findings

- No concerning change in usual headache pattern

- No high-risk comorbid conditions (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus infection)

- No new concerning historical or physical examination finding

Migraine without aura:

Diagnostic criteria: (2)

A. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B–D

B. Headache attacks lasting 4–72 hours (when untreated or unsuccessfully treated)

C. Headache has at least two of the following four characteristics:

- unilateral location

- pulsating quality

- moderate or severe pain intensity

- aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity (e.g., walking or climbingstairs)

D. During the headache, at least one of the following:

- nausea and/or vomiting

- photophobia and phonophobia

- Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Migraine with aura:

Diagnostic criteria: (2)

A. At least two attacks fulfilling criteria B and C

B. One or more of the following fully reversible aura

symptoms:

- visual

- sensory

- speech and/or language

- motor

- brainstem

- retinal

C. At least three of the following six characteristics:

- at least one aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes

- two or more aura symptoms occur in succession

- each aura symptom lasts 5–60 minutes1

- at least one aura symptom is unilateral

- at least one aura symptom is positive

- the aura is accompanied or followed within

60 minutes, by headache

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Tension-type headache:

Diagnostic criteria: (Infrequent episodic tension-type headache) (2)

A. At least ten episodes of headache occurring on <1 day/month on average (<12 days/year) and fulfilling criteria B–D

B. Lasting from 30 minutes to seven days

C. At least two of the following four characteristics:

- bilateral location

- pressing or tightening (non-pulsating) quality

- mild or moderate intensity

- not aggravated by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs

D. Both of the following:

- no nausea or vomiting

- no more than one of photophobia or phonophobia

E. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Cluster headache:

Diagnostic criteria: (2)

A. At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B–D

B. Severe or very severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain lasting 15–180 minutes (when untreated)

C. Either or both of the following:

1. at least one of the following symptoms or signs, ipsilateral to the headache:

a) conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation

b) nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea

c) eyelid edema

d) forehead and facial sweating

e) miosis and/or ptosis

2. a sense of restlessness or agitation

Occurring with a frequency between one every

other day and eight per day

E. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Table 2. Management of most common primary headaches: (1)

| Condition | First-line treatment | Second-line treatment | Discharge key points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tension-type | Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, antiemetics | Sumatriptan, opioids | Close follow-up with primary care physician/neurologist. Written instructions and red flags for emergent consultation |

| Migraine | Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, antiemetics, dark room | Sumatriptan, ergotamine derivatives, opioids | Close follow-up with primary care physician/neurologist. Written instructions and red flags for emergent consultation |

| Cluster | Sumatriptan, antiemetics, oxygen therapy | Opioids | Close follow-up with primary care physician/neurologist. Written instructions and red flags for emergent consultation |

Disclosures

The author does not report any conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This information is for educational purposes, not to treat disease or supplant professional medical judgment. Physicians should follow local policy regarding the diagnosis and management of medical conditions.

See Also

An Overview of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Acute Vestibular Symptoms: an Approach to Diagnosis and Management

References

- Luciani M, Negro A, Spuntarelli V, Bentivegna E, Martelletti P. Evaluating and managing severe headache in the emergency department. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2021 Mar 4;21(3):277-85.

- Arnold M. Headache classification committee of the international headache society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211.

- Rizzoli P, Mullally WJ. Headache. Am J Med. 2018 Jan;131(1):17-24.

- Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2018 Apr;58(4):496-505.

- Straube A, Andreou A. Primary headaches during lifespan. The journal of headache and pain. 2019 Dec;20(1):1-4.

- Jensen RH. Tension‐type headache–the normal and most prevalent headache. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2018 Feb;58(2):339-45.

- Abu Bakar N, Tanprawate S, Lambru G, Torkamani M, Jahanshahi M, Matharu M. Quality of life in primary headache disorders: a review. Cephalalgia. 2016 Jan;36(1):67-91.

- Polson M, Williams TD, Speicher LC, Mwamburi M, Staats PS, Tenaglia AT. Concomitant medical conditions and total cost of care in patients with migraine: a real-world claims analysis. Am J Manag Care. 2020 Feb 1;26(1 Suppl):S3-7.

- Casas Parera, I. Carmona, S. Campero, A. Manual de Neurologia, 3ra edición. Buenos Aires: Alfaomega; 2011. p. 165-166.

- Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, Schankin C, Nelson SE, Obermann M, Hansen JM, Sinclair AJ, Gantenbein AR, Schoonman GG. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology. 2019 Jan 15;92(3):134-44.

- Munoz-Ceron J, Marin-Careaga V, Peña L, Mutis J, Ortiz G. Headache at the emergency room: Etiologies, diagnostic usefulness of the ICHD 3 criteria, red and green flags. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 7;14(1):e0208728.

- Nordhaug LH, Hagen K, Vik A, Stovner LJ, Follestad T, Pedersen T, Gravdahl GB, Linde M. Headache following head injury: a population-based longitudinal cohort study (HUNT). The journal of headache and pain. 2018 Dec;19(1):1-9.

- Lucas S, Hoffman JM, Bell KR, Walker W, Dikmen S. Characterization of headache after traumatic brain injury. Cephalalgia. 2012 Jun;32(8):600-6.

- Bhoi SK, Jha M, Chowdhury D. Advances in the Understanding of Pathophysiology of TTH and its Management. Neurology India. 2021 Mar 1;69(7):116.

- Faraji F. Tension-type headache. Headache and Migraine in Practice. 2022 Jan 1:75-83.

- Ashina S, Mitsikostas DD, Lee MJ, Yamani N, Wang SJ, Messina R, Ashina H, Buse DC, Pozo-Rosich P, Jensen RH, Diener HC. Tension-type headache. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2021 Mar 25;7(1):1-21.

- García-Azorín D, Farid-Zahran M, Gutiérrez-Sánchez M, González-García MN, Guerrero AL, Porta-Etessam J. Tension-type headache in the Emergency Department Diagnosis and misdiagnosis: The TEDDi study. Scientific reports. 2020 Feb 12;10(1):1-8.

- Ashina S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M. Pathophysiology of migraine and tension-type headache. Techniques in regional anesthesia and pain management. 2012 Jan 1;16(1):14-8.

- Steel SJ, Robertson CE, Whealy MA. Current understanding of the pathophysiology and approach to tension-type headache. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2021 Oct;21(10):1-2.

- Dodick DW. A phase‐by‐phase review of migraine pathophysiology. Headache: the journal of head and face pain. 2018 May;58:4-16.

- Gross EC, Lisicki M, Fischer D, Sándor PS, Schoenen J. The metabolic face of migraine—from pathophysiology to treatment. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2019 Nov;15(11):627-43.

- McGeeney BE. Cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. InSeminars in Neurology 2018 Dec (Vol. 38, No. 06, pp. 603-607). Thieme Medical Publishers.

- Nahas SJ. Cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2021 Jun 1;27(3):633-51.

- Mares C, Dagher JH, Harissi-Dagher M. Narrative review of the pathophysiology of headaches and photosensitivity in mild traumatic brain injury and concussion. Canadian journal of neurological sciences. 2019 Jan;46(1):14-22.

- Schwedt TJ. Post-traumatic headache due to mild traumatic brain injury: current knowledge and future directions. Cephalalgia. 2021 Apr;41(4):464-71.

- Harriott AM, Karakaya F, Ayata C. Headache after ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2020 Jan 7;94(1):e75-86.

- Diener HC, Katsarava Z, Weimar C. Headache associated with ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Revue neurologique. 2008 Oct 1;164(10):819-24.

- Rajashekar D, Liang JW. Intracerebral hemorrhage. InStatPearls [Internet] 2021 Jul 26. StatPearls Publishing. [Cited 9/17/2022]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553103/

- Carolei A, Sacco S. Headache attributed to stroke, TIA, intracerebral haemorrhage, or vascular malformation. InHandbook of Clinical Neurology 2010 Jan 1 (Vol. 97, pp. 517-528). Elsevier.

- Men Puthik and Le Van Tuan. Headache in acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage. Joint Event on International Conference on Neuroimmunology, Neurological disorders and Neurogenetics & 28th World Summit on Neurology, Neuroscience and Neuropharmacology. Montreal, Canada: September 26-27. [cited September 17, 2022]. Available from: https://www.iomcworld.org/proceedings/headache-in-acute-phase-of-intracerebral-hemorrhage-50173.html.

- Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. The Lancet. 2017 Feb 11;389(10069):655-66.

- Swadron SP. Pitfalls in the management of headache in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Clinics. 2010 Feb 1;28(1):127-47.

- Connolly Jr ES, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, Hoh BL, Kirkness CJ, Naidech AM, Ogilvy CS, Patel AB. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012 Jun;43(6):1711-37.

- Murthy SB, Wu X, Diaz I, Parasram M, Parikh NS, Iadecola C, Merkler AE, Falcone GJ, Brown S, Biffi A, Ch’ang J. Non-traumatic subdural hemorrhage and risk of arterial ischemic events. Stroke. 2020 May;51(5):1464-9.

- Gao L, Xu W, Li T, Yu X, Cao S, Xu H, Yan F, Chen G. Accuracy of magnetic resonance venography in diagnosing cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Thrombosis research. 2018 Jul 1;167:64-73.

- Luo Y, Tian X, Wang X. Diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: a review. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2018 Jan 30;10:2.

- Debette S, Compter A, Labeyrie MA, Uyttenboogaart M, Metso TM, Majersik JJ, Goeggel-Simonetti B, Engelter ST, Pezzini A, Bijlenga P, Southerland AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of intracranial artery dissection. The Lancet Neurology. 2015 Jun 1;14(6):640-54.

- Debette S, Mazighi M, Bijlenga P, Pezzini A, Koga M, Bersano A, Kõrv J, Haemmerli J, Canavero I, Tekiela P, Miwa K. ESO guideline for the management of extracranial and intracranial artery dissection. European stroke journal. 2021 Sep;6(3):XXXIX-LXXXVIII.

- Ellis JA, Munne JC, Lavine SD, Meyers PM, Connolly Jr ES, Solomon RA. Arteriovenous malformations and headache. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2016 Jan 1;23:38-43.

- Osgood ML. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Review of the pathophysiology and management strategies. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2021 Sep;21(9):1-1.

- Chacko JG, Chacko JA, Salter MW. Review of giant cell arteritis. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 2015 Jan 1;29(1):48-52.

- Serling-Boyd N, Stone JH. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Current opinion in rheumatology. 2020 May;32(3):201.

- Peng KP, Fuh JL, Wang SJ. High-pressure headaches: idiopathic intracranial hypertension and its mimics. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2012 Dec;8(12):700-10.

- Hadidchi S, Surento W, Lerner A, Liu CS, Gibbs WN, Kim PE, Shiroishi MS. Headache and brain tumor. Neuroimaging Clinics. 2019 May 1;29(2):291-300.

- Kim JE, Kim SH, Han RJ, Kang MH, Kim JH. Postdural puncture headache related to procedure: incidence and risk factors after Neuraxial anesthesia and spinal procedures. Pain Medicine. 2021 Jun;22(6):1420-5.

- Tai CS, Wu SL, Lin SY, Liang Y, Wang SJ, Chen SP. The causal-effect of bed rest and post-dural puncture headache in patients receiving diagnostic lumbar puncture: A prospective cohort study. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2021 Aug 1;84(8):791-4.

- Young N, Thomas M. Meningitis in adults: diagnosis and management. Internal medicine journal. 2018 Nov;48(11):1294-307.

- Thy M, Gaudemer A, d’Humières C, Sonneville R. Brain abscess in immunocompetent patients: recent findings. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2022 Jun 1;35(3):238-45.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 May 15;71(19):e127-248.

- Rodriguez MA, Kumar SK, De Caro M. Hypertensive crisis. Cardiology in review. 2010 Mar 1;18(2):102-7.

- Galgano M, Toshkezi G, Qiu X, Russell T, Chin L, Zhao LR. Traumatic brain injury: current treatment strategies and future endeavors. Cell transplantation. 2017 Jul;26(7):1118-30.

- Zufiría JM, Prieto NL, Cuba BC, Degenhardt MT, Núñez PP, Serrano MR, Raigada AB. Traumatismo craneoencefálico leve. Surgical Neurology International. 2018;9(Suppl 1):S16.

- Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019 Dec;50(12):e344-418.

- Greenberg SM, Ziai WC, Cordonnier C, Dowlatshahi D, Francis B, Goldstein JN, Hemphill III JC, Johnson R, Keigher KM, Mack WJ, Mocco J. 2022 guideline for the management of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2022 Jul;53(7):e282-361.

- Gerard C, Busl KM. Treatment of acute subdural hematoma. Current treatment options in neurology. 2014 Jan;16(1):1-5.

- Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti ML, Bullard MJ, Hohl CM, Sutherland J, Émond M, Worster A, Lee JS, Mackey D, Pauls M. Clinical decision rules to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage for acute headache. Jama. 2013 Sep 25;310(12):1248-55.

- Dubosh NM, Bellolio MF, Rabinstein AA, Edlow JA. Sensitivity of early brain computed tomography to exclude aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016 Mar;47(3):750-5.

- Gorchynski J, Oman J, Newton T. Interpretation of traumatic lumbar punctures in the setting of possible subarachnoid hemorrhage: who can be safely discharged?. The California Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2007 Feb;8(1):3.

- Maher M, Schweizer TA, Macdonald RL. Treatment of spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage: guidelines and gaps. Stroke. 2020 Apr;51(4):1326-32.

- Wu WT, Pan HY, Wu KH, Huang YS, Wu CH, Cheng FJ. The Ottawa subarachnoid hemorrhage clinical decision rule for classifying emergency department headache patients. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2020 Feb 1;38(2):198-202.

- Hainer BL, Matheson EM. Approach to acute headache in adults. American family physician. 2013 May 15;87(10):682-7.

- Murray D. Emergency management: angle-closure glaucoma. Community eye health. 2018;31(103):64.

Follow us